Introduction

Metastatic involvement of the skull base is a well-known complication of a variety of systemic cancers. In these cases, the clinical diagnosis is usually suspected by the presence of symptoms

and signs secondary to the involvement of cranial nerves that exit

through the basal foramina, together with persistent headache.

The orbital, parasellar, middle fossa, jugular foramen and Occipital Condyle Syndrome (OCS) were the five clinical syndromes

associated with skull base metastases described by Greenberg et

al in 1981[1]. The OCS is characterized by unilateral occipital pain

and unilateral tongue paralysis. Although a group of patients with

OCS have a benign explanation, such as trauma, infection, stroke

and Guillain-Barré syndrome, a wide variety of malignancies account for the remainder of cases of OCS. In fact, in these cases, the OCS is usually the first clinical manifestation of the neoplasm.

We report the first case of OCS associated with a malignant insulinoma.

Case report

This 57 year-old woman began in 2005 with recurrent neurological symptoms associated with hypoglycemia. A CT scan demonstrated a pancreatic mass. She underwent distal pancreatectomy

and splenectomy, and the histopathological examination of the

excised tissue revealed a pancreatic insulinoma. At that time, hepatic islet cell metastases were observed. The liver metastases

had no change after two chemoembolizations with polyvinyl alcohol particles and treatment with octreotide and diazoxide was administered. In 2009, she underwent liver transplantation for the

metastatic neuroendocrine tumour with no incidences. She was on tacrolimus, which was changed to everolimus one year later.

Two years after liver transplantation, a CT scan of the abdomen

disclosed peritoneal, lymph node and hepatic metastases and capecitabine was added. Five days before his admission in February

2010, the patient began to have dysarthria, dysphagia, and progressive left occipital pain. He complained of severe, continuous,

left occipital pain that became unbearable with left suboccipital

palpation or on neck rotation to the right. Routine analgesics were

of no help and morphine was administered to control pain. There

were no cervical masses on palpation. Neurological abnormalities

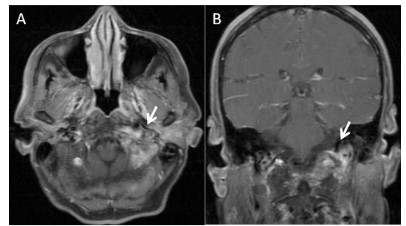

were limited to left hypoglossal nerve paralysis. An osteolytic lesion was found in the left clavicle by a thoracic CT examination. An

MRI study of the skull base showed an enhancing soft tissue mass

close to the left foramen magnum without intracranial invasion

(Figure 1). A brain MRI was found to be normal. His general status

deteriorated, and the patient died one week later.

Discussion

Insulinoma is a rare neuroendocrine tumour with an annual

incidence of 0.4 cases per 100 000 people. Insulinoma has malignant characteristics defined by metastases in only 10% of the

cases [2,3]. Most patients with malignant insulinoma have lymph

node or liver metastases and only rarely involve other organs,

such the skeletal system. The available treatments show only

short-term benefits and the prognosis of these patients is relatively poor with a median survival period of approximately 2 years

[2]. Insulinoma could be a feature of multiple endocrine neoplasia

type 1 (MEN1) and approximately 4% of patients with insulinoma

will have MEN1; in this case is very unlike a MEN1-associated insulinoma based on the absence of a family history of MEN 1 and

the absence of other clinical, biochemical or radiological characteristics of MEN 1 [4]. Due to the small number of patients with

malignant insulinoma, there are little data regarding its neurological complications. Neurological symptoms are frequent in the

initial phases of insulinoma. Hypoglycemia due to insulinomas mimics a great variety of neurological conditions and most patients

with present with neurological or psychiatric manifestations that

often lead to misdiagnosis. Symptoms from central nervous system glucose deprivation could persist for years since the diagnosis due to unregulated secretion of insulin and proinsulin-related

products from malignant insulinoma [5,6]. In addition, peripheral

neuropathy is unusually reported as a neurological complication

in the course of insulinoma probably due to maintained hypoglycemia rather than secondary to hyperinsulinaemia [7]. To our

knowledge, no other neurological features of insulinoma have been reported except symptoms due to hypoglycemia of either

the central or peripheral nervous system.

The hypoglossal nerve arises from the motor nucleus located

beneath the floor of the fourth ventricle, passing in front of the

vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries. It exits the

base of the skull through the hypoglossal canal in the occipital

bone; it then traverses the neck and curves back, divides and innervates the tongue muscles. Metastatic involvement of the occipital condyle originates the OCS, which is characterized by unbearable unilateral occipital pain and ipsilateral tongue paralysis.

Several malignant causes have been described as a cause of OCS,

including metastases from different types of tumours [1,8-15].

but we have found no reference in the English language literature

to isolated hypoglossal neuropathy caused by insulinoma metastases to the base of the skull.

When OCS is suspected based on its stereotyped symptoms, CT

and MRI are the diagnostic steps. The MRI is better for delineating

soft tissues. The sections of CT and MRI must be low enough to

show the foramen magnum area to detect the suspected lesion.

In patients with skull base metastases known to have untreatable

cancer, local palliative radiation therapy should be undertaken

as soon as possible [16]. When this treatment is delivered early,

symptomatic relief can be expected in most patients. In patients

without known systemic cancer, skull base metastases can be the

first manifestation of neoplasia and a search for a primary source

is indicated in patients with OCS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we added malignant insulinoma as a cause of

OCS; clinicians should keep in mind the diagnosis of OCS even in

tumours for which OCS has not been reported in the literature. In

addition, this description of malignant insulinoma contributes to

a better understanding of its clinical course to clarify the role of

therapeutic procedures in the disease.

References

- Greenberg HS, Deck MD, Vikram B, Chu FC, Posner JB. Metastasis

to the base of the skull: clinical findings in 43 patients. Neurology.

1981; 31: 530-537.

- Mathur A, Gorden P, Libutti SK. Insulinoma. Surg Clin North Am.

2009; 89: 1105-1121.

- Sada A, Glasgow AE, Vella A, Thompson GB, McKenzie TJ, et al. Malignant Insulinoma: A Rare Form of Neuroendocrine Tumor. World

J Surg. 2020; 44: 2288-2294.

- Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, Bilezikian J, Dralle H,et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1

(MEN1). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97: 2990-3011.

- Ding Y, Wang S, Liu J, Yang Y, Liu Z, et al. Neuropsychiatric profiles

of patients with insulinomas. Eur Neurol. 2010; 63: 48-51.

- Shaw C, Haas L, Miller D, Delahunt J. A case report of paroxysmal

dystonic choreoathetosis due to hypoglycaemia induced by an insulinoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996; 61: 194-195.

- Tintoré M, Montalbán J, Cervera C, et al. Peripheral neuropathy

in association with insulinoma: clinical features and neuropathology of a new case. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994; 57: 1009-

1010.

- Takeuchi S, Osada H, Nagatani K, Shima K. Occipital condyle syndrome as the first sign of skull metastasis from lung cancer. Asian J

Neurosurg. 2017; 12: 145-146.

- Marruecos J, Conill C, Valduvieco I, Vargas M, Berenguer J, et al.

Occipital condyle syndrome secondary to bone metastases from

rectal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol Off Publ Fed Span Oncol Soc Natl

Cancer Inst Mex. 2008; 10: 58-60.

- Capobianco DJ, Brazis PW, Rubino FA, Dalton JN. Occipital condyle

syndrome. Headache. 2002; 42: 142-146.

- Morís G, Roig C, Misiego M, Alvarez A, Berciano J, et al. The distinctive headache of the occipital condyle syndrome: a report of four

cases. Headache. 1998; 38: 308-311.

- Moeller JJ, Shivakumar S, Davis M, Maxner CE. Occipital condyle

syndrome as the first sign of metastatic cancer. Can J Neurol Sci J

Can Sci Neurol. 2007; 34: 456-459.

- Rodríguez-Pardo J, Lara-Lara M, Sanz-Cuesta BE, Fuentes B, DíezTejedor E. Occipital Condyle Syndrome: A Red Flag for Malignancy.

Comprehensive Literature Review and New Case Report. Headache. 2017; 57: 699-708.

- Salamanca JIM, Murrieta C, Jara J, Munoz-Blanco JL, Alvarez F, et

al. Occipital condyle syndrome guiding diagnosis to metastatic

prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2006; 13: 1022-1024.

- Saraswat MK, Perera RW, Renwick I, Zuromskis T, Singh V, et al.

Occipital condyle syndrome: self diagnosed. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;

2009: bcr08.2008.0636.

- Rades D, Schild SE, Abrahm JL. Treatment of painful bone metastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010; 7: 220-229.