Introduction

Weak uterine contractions during cesarean section are the

most common cause of Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) [1], accounting for 70-80% of cases, with a progressive increase [2-4],

For weak uterine contractions in addition to the first use of uterine

contraction agents, when they are ineffective, surgical treatment

needs to be used as early as possible [5,6]. The B-Lynch method

of uterine loop suturing and intrauterine balloons Intrauterine

Balloons (IUB) are relatively easy and commonly used methods

to stop bleeding, but in recent years complications associated

with uterine loop suturing have been reported, such as myometrial damage necrosis, catastrophic uterine rupture in mid to late

pregnancy, uterine adhesions, secondary infertility, etc., causing

pelvic and abdominal adhesions and bringing about a significantly

higher incidence of complications [7-12]. Recently, in our hospital,

due to intraoperative uterine contraction weakness after using

circumferential suturing caused partial ischemic necrosis of the

uterus and secondary infection, the patient was treated conservatively for up to 6 months and eventually the ischemic necrotic

tissue of the uterus gradually returned to normal and the infection was controlled, the clinical data of this patient combined with

literature review is reported below.

Case information

Female, 26 years old, primigravida. The pregnancy was terminated by cesarean section due to social factors, intraoperatively

the uterus was weakly contracted after placental spontaneous

abruption, and she was given 20 U of contractin, 2 ml of motherwort uterine body injection, 0. 2 mg of ergometrine maleate

injection drip, 2 layers of myometrium were continuously sutured with barbed sutures, and 1 layer of plasma myometrium was

continuously sutured with barbed sutures, the uterus was still

weakly contracted like a sack, continuous massage of the uterus

was ineffective, she was given 0. 9% NS+ The uterus contraction

was still not improved, the uterus was quickly delivered outside

the abdominal cavity, and the uterus was circumferentially sutured and tied with 1-0 absorbable thread in the non-vascular

area of the broad ligament of the parametrium for 3 times with

an interval distance of about 5.0 cm, the uterus was observed to

be circumferential in shape, the uterus was normal in color, and

no blood was oozing from the suture eyes, and the uterus was

placed into the The pelvic cavity was explored and the abdomen

was closed after the uterine incision suture was free of blood and

the bilateral adnexa were free of abnormalities. On postoperative day 4, he developed fever and was treated with ceftazidime

+ ornidazole. On postoperative day 11, he was still febrile, and the culture result of vaginal secretion suggested Escherichia coli

(+). Moxifloxacin + Ornidazole triple anti-infection. On the 13th

postoperative day, fever was still present, and in order to be alert

to potential fungal infection, the medication was adjusted to the

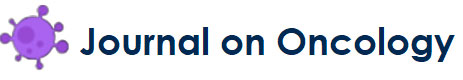

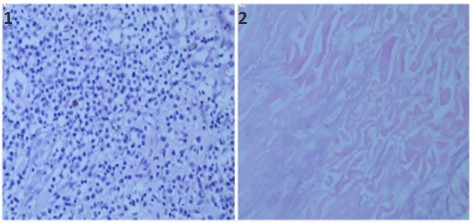

combination of meropenem + voriconazole anti-infective treatment. No fever was observed after the 15th postoperative day. Relevant postoperative ancillary tests are shown in Figures 1, 2

and 3 below.

Table 1: Postoperative antibiotic use in this case.

| Time (post-operative) |

Fever |

Antibiotics |

| the same day |

not |

Cefuroxime sodium |

| 4 d |

have |

Ceftazidime + Ornidazole |

| 11 d |

have |

Ceftazidime + Ornidazole + Levofloxacin |

| 12 d |

have |

Meropenem + Moxifloxacin + Ornidazole |

| 13 d |

have |

Meropenem + voriconazole |

| 15 d |

not |

Meropenem + voriconazole |

Table 2: Post-operative review of the mother in this case.

| Time

(post-operative) |

Magnetic resonance results |

Time

(post-operative) |

Color ultrasound results |

| 11 d |

The uterus is enlarged and the wall thickened, with

fascicular changes seen in the fundic-body junction area,

which is poorly defined. |

34 d |

The uterine body measures approximately 98 x 89 x 59 mm, and

an inhomogeneous echogenic mass measuring approximately 65

x 66 x 45 mm is seen in the uterine cavity. |

| 15 d |

The uterus was enlarged, wall thickened, and fasciculated

changes were seen in the fundic-body junction area,

which was reduced from the previous subserosal cystic

lesion within the uterus. |

48 d |

The uterine body is approximately 78 x 89 x 55 mm in size, and

an inhomogeneous hyperechoic mass of 55 x 77 x 50 mm in size

is seen in the uterine cavity. |

| 25 d |

The uterus was enlarged and wall thickened, with

fascicular changes seen in the fundus-body junction area,

64 mm in diameter; the cystic lesion was reduced from

the previous fundus and body of the uterus. |

67 d |

The size of the uterine body was about 67 x 61 x 37 mm and the

size of the inhomogeneous hyperechoic mass was seen in the

uterine cavity about 51 x 47 x 29 mm. |

| 59 d |

The uterus is slightly enlarged and a round-like cystic long

T2 signal of approximately 44X39X6 2mm is seen at the

base of the uterus, which is reduced from the previous

cystic lesion at the base of the uterus. |

125 d |

The size of the uterine body is about 31 x 39 x 35 m, and a mixed

echogenic area with a range of about 28 x 13 m is seen in the

middle and lower part of the uterine cavity. |

| 188 d |

The uterus was not abnormal in size or morphology,

and the bottom wall was seen to be 12m m in diameter

isosignal; it was significantly smaller than the previous

fundal uterine lesion. |

188 d |

The size of the uterine body was about 34 x 37 x 27 mm, and an

area of 11 x 6 mm inhomogeneous echogenicity was seen within

the myometrium at the lower anterior wall incision. |

Discussion

Uterine contraction weakness refers to the weakness of uterine contraction, as the most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage, and is also an indication for uterine compression suture [4], the basis of this suture technique used in surgery is from

the British scholar B-Lynch proposed in 1997 [13], it belongs to a

kind of uterine body compression suture, through the compression of the uterine cavity, reduce the volume of the uterine cavity

to achieve the purpose of hemostasis, mainly used for bleeding

caused by contraction weakness of the uterine body part, currently based on this suture technique has been derived from surgical

sutures used in different ranges and with different advantages

and disadvantages [14,15], such as Haymen modification of the

B-Lynch suture technique, Cho square suture (patch suture, multi-square pressure suture), Hwu suture (patch suture, multi-square

pressure suture), Hwu suture (parallel vertical compression suture of the lower uterine segment), etc. In this case, the patient

developed partial ischemic necrosis of the myometrium and secondary infection after circumferential binding suture of the uterus, and the early antibiotics used failed to control the infection

effectively. Therefore, in similar rare cases when infection cannot

be effectively controlled with conventional antibiotics, whether

early prophylactic use of antifungal drugs would bring unexpected anti-infective effects and perhaps better improve the patient's

postoperative recovery, and avoid the occurrence of infection.

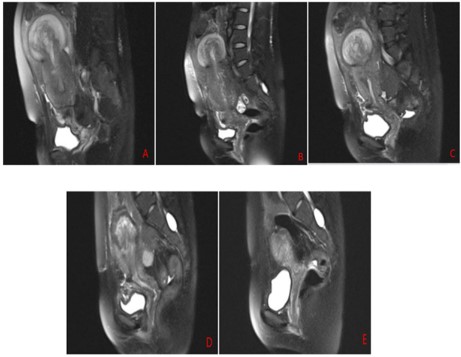

After postoperative imaging data, hysteroscopy and pathological

examination all suggest the presence of defective necrotic lesions

in the uterus and the presence of infection in the uterine cavity,

whether hysterectomy must be performed to resolve the symptoms of ischemic necrosis and infection when imaging and related ancillary examinations and clinical symptoms suggest the presence of ischemic necrosis and co-infection, after the availability

of hysterectomy guidelines [4], it is still necessary to For patients

who are primiparous or have high fertility requirements, and

whose clinical symptoms have gradually decreased after surgery

and whose lesions have gradually decreased in size and normalized on relevant ancillary tests, continued conservative treatment

under close monitoring is also a better option. Ischemic necrosis

of the uterus complicated by infection as one of the complications

after cricothyrotomy [4], this patient as a rare clinical case, after

ischemic necrosis of the uterus and secondary infection through

up to six months of conservative treatment, not only the infection was controlled, ischemic necrosis of the uterus lesion also

gradually shrunk and returned to normal, although avoiding hysterectomy, but for our clinical treatment of such cases brings reflections, for intraoperative uterus due to Although hysterectomy

was avoided, it brings reflections on our clinical treatment of such

cases. For patients who underwent uterine cricothyrotomy due to

weak intraoperative contraction, more attention should be paid

to postoperative condition monitoring, clinical treatment, and clinical care to achieve early monitoring, early treatment, and early

management to facilitate postoperative recovery.

References

- Ma HW, Liu XH. Changes in the etiological composition of postpartum hemorrhage and countermeasures. Journal of Practical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 20 21; 37: 165-168.

- Bateman BT, Berman MF, Riley LE, Leffert LR. The epidemiology of

postpartum hemorrhage in a large, nationwide sample of deliveries. Anesth Analg. 2011; 31: 89.

- Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, et al. lncidence, risk factors, and

temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 2013; 209: 449.

- Joseph KS, Rouleau J, Kramer MS, Young DC, Liston RM, et al. Investigation of an increase in postpartum haenordlage in Canada.

BJOG. 2007; 114: 751.

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Group of the Chinese Medical Association, Obstetrics and Gynecology Branch. Guidelines for the prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014; 49: 641-646.

- Liu XH, He R. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Chinese Journal of Practical Gynecology and Obstetrics.

2020; 36: 123-126.

- Cotieb AG, Pandipati S, Davis KM, Gibbs RS. Uerine necrosis:a complication of uterine compression sutures. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;

112: 429-431.

- Ibrahim MI, Raafat TA. Elaithy MI. Risk of postpartum uterine synechiae following uterine compression suturing during pospartum

hemorrhage. Aust N z J Ohmtet Gynacol. 2013; 53: 37-45

- Jiang L, Yang F, Yang F. A cease repont of complications fllowing a

combination of modulated B-lynch and Hwu sutures in postpartum hemorrhage: haematocele in the uterine cavity, hemoperitoneum and swelling and nupture of the fallopian tube. J Obstet

Gynaccol. 2019; 39: 115-117.

- Pechtor K. Richards B. Paterson H. Antenatal eatastophic uterine

rupture at 32 weeks of gestation after previous B-Lynch suture.

BJOG. 2010; 117: 889-891.

- An GH, Ryu HM, Kim MIY, Han JY, Chung JH, et al. Outcomes of

subsequent pregnancies after uterine compression sutures for

postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 122: 565-570.

- Date s, Murthy B, Maglum A. Pot B-lynch uterine rupture: ease report and review of literature. J Obstet Gymeeol. 2014; 64: 362-363.

- B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, Abu J, Cowen MJ. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive post-partum hemorrhage:

an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases re- ported. Br J Obstet

Gynaecol.1997; 104: 372-375.

- Kayem G, Kurinczuk JJ, Alfirevic Z, Spark P, Brocklehurst P, et al.

Specific second-line therapies for postpartum hemorrhage: a national cohort study. BJOG. 2011; 118: 856-864.

- Zhang GH, Shen XY, Cui WH. Etiology finding, joint management

and prevention and control of disseminated intravascular coagulation in secondary uterine contractile bleeding. Chinese Journal of

Practical Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2022; 38: 161-164.