Introduction

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GISTs) are the most common

mesenchymal tumors of the alimentary tract; they arise from the

interstitial cells of Cajal [1], pacemaker cells interposed between

the smooth muscle cells of the digestive tract and intramural neurons and characterized by the over expression of tyrosine kinase

receptor C-Kit [2], (CD117), a type III tyrosine kinase receptor for

stem cell growth factor, were found to be the source of GISTs [3].

GISTs can associate on other mutations [5,6]: about 5% of cases

are part of family genetic syndromes. The most common site of involvement is the stomach (56%), which is characterised by a better prognosis, followed by the small intestine (32%) and then the

colon and rectum (6%) [1], although they can occur at any level of

the digestive tract and occasionally in the omentum, mesentery

and peritoneum. Most cases of GISTs are sporadic. The correct

diagnosis of GIST is determined by histopathological examination

and immunohistochemistry [7].

They are frequently asymptomatic and may be detected incidentally on imaging studies for other indications. In particular

small size GISTs are usually asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally on radiological imaging for a different purpose or during

an endoscopic exploration, or during surgery. Large tumors may

cause abdominal distention, compression of the gastrointestinal

tract (for example GISTs with exophytic growth) or obstruction

of the gastrointestinal lumen (tumors with endophytic growth).

Symptomatic GISTs often make patient suffer from early satiety,

vague abdominal discomfort, nausea, upper GI bleeding, producing anemia and melena. Clinical manifestations are based on size

and tumor location. In the absence of complications, such as upper digestive hemorrhage/hemoperitoneum, intestinal obstruction, tumor perforation, or obstructive jaundice, the symptoms

are nonspecific (anemia, early satiety, swelling, abdominal pain)

[8]. The most common manifestation is gastrointestinal bleeding,

accompanied by anemia, hematemesis or melena. Dysphagia is

the main symptom encountered in esophageal GISTs. Furthermore, metastases can occur in advanced stages.

Suspected GISTs are usually evaluated with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans; CT scan

remains the preferred initial imaging method used for staging the

disease. The lesion appear as hypervascular, heterogenous, and

enhancing masses, which displace rather than invade adjacent organs., They appear as smooth submucosal elevations on upper GI

endoscopy. Although endoscopy is useful to characterize and locate the lesion, biopsies rarely obtain adequate tissue to confirm

the diagnosis. Endoscopic ultrasound can confirm the origin of

the tumor from the submucosal layer and allow for image-guided,

deep sampling. In GISTs found in specific locations (e.g., the rectum) or in evaluating the anatomical extension of surgery, MRI

may be a better imaging option [9].

The survival rate of patients with GIST depends on multiple

factors: recurrence after treatment, risk category, GIST stage, or

treatment applied. Thus, patients with localized GISTs have a 5-year life expectancy of 93%, while patients with locally advanced

GISTs have a 5-year survival rate of 80%, and those with metastatic GISTs of 55% [4]. Risk stratification of GISTs attempts to define the risk of a poor outcome and to identify patients who may

benefit from adjuvant therapy.

Clinically, the classification scores by Fletcher et al. And Miettinen and Lasota are the most widely accepted ones. Fletcher et

al. classify the risk of aggressive evolution in four classes, depending on mitotic rate and tumor size:

• Very low risk: tumoral size <2 cm; mitotic count <5/50 high-power field;

• Low risk: tumoral size 2–5 cm; mitotic count <5/50 high-power field;

• Intermediate risk: tumoral size <5 cm and mitotic count

6–10/50 high-power field, or tumoral size 5–10 cm and mitotic count <5/50 high-power field;

• High risk: tumoral size >5 cm and mitotic count >5/50 high-power field, or tumoral size >10 cm and any mitotic rate, or

any tumoral size and mitotic rate >10/50 high-power field

[10].

Compared to GISTs that are localized in the small intestine or

rectum, gastric localization of GISTs is associated with a better

prognosis [11].

Surgical treatment

The role of minimal invasive surgery has been growing in recent years, while traditionally, open surgery has been advocated

for GISTs, expecially for fear of peritoneal seeding. The use of a

transgastric approach avoids the potential complication of luminal stenosis following a wedge resection of a tumor close to the

cardia. Local invasion is uncommon so that lymphadenectomies

are rarely required: a wide local resection is usually curative. Irrespective of tumor size, a laparoscopic approach can be considered

as the first line in uncomplicated GISTs [1]. Laparoscopic approach

is safe and feasible for Gastric GIST both in urgent and elective

settings. Laparoscopy shows a recurrence rate similar to open

surgery when radical resection are performed, even for lesions

greater than 5 cm. It is important to take in consideration the very

surgical team experience, one of the most important factors reducing the incidence of operative complications with better longterm outcomes, both oncological and postoperative [2]. While

traditionally, open surgery has been advocated for GISTs, for fear

of peritoneal seeding, the role of minimal access surgery has been

growing in recent years. The use of a transgastric approach avoids

the potential complication of luminal stenosis following a wedge

resection of a tumor close to the cardia. Because lymphadenectomies are rarely required and local invasion is uncommon, a wide

local resection is usually curative. Thus, a laparoscopic approach

can be considered as the first line in uncomplicated GISTs, irrespective of tumor size [1]. A wide, local resection with a 1 to 2

cm margin may be considered adequate. Additionally, a stapled

wedge gastrectomy would lead to a loss of significant uninvolved

gastric wall with the potential for significant luminal compromise.

It has also been seen that the margin of resection does not significantly affect the outcome, with similar recurrence-free survival in

patients who had R0 or R1 resections.

One potential shortcoming of transgastric approach is com-

promising the vascularity of the greater curvature, which can lie

between two longitudinal gastric incisions. It is usefull to confirm

adequate vascularity of the greater curvature in patients with the

use of indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence angiography.

Histopatology

The section surface may be homogeneous, seen mostly in

small-size GISTs, or heterogeneous, with areas of hemorrhage

and necrosis in larger tumors. In small tumors, the coating mucosa remains unchanged (appearing normal), but in large, more

aggressive tumors, it may ulcerate. There are three main types of

GISTs: spindle cell type (70%), epithelioid type (20%) and mixed

type (10%) [3]. These tumors may range from small, benign lesions to large, hemorrhagic and necrotic masses with metastases.

Macroscopically, GISTs are well-defined, firm consistency, white in

color and not encapsulated [7].

Case report

Here we report a case of a 80-year-old female patient who was

being evaluated for weakness, anemia, and hematemesis.

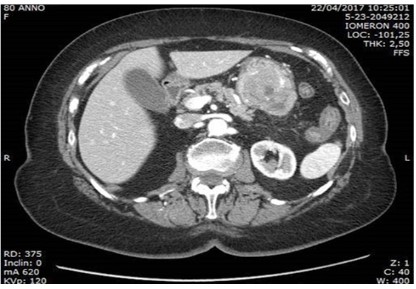

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) confirmed the presence of a voluminous ETP-like lesion, intensely capturing contrast

medium, of about 6 cm in maximum diameter, apparently originating from the submucosa of the gastric body, with extra-parietal

extension at the level of the great gastric curve, and with erosion

of the mucosa on the internal side. Hyperdense material is detected inside the gastric lumen as from bleeding in progress and in the

arterial phase the lesion appears vascularized by a large arterial

feeder starting from the A. gastric. No significant lymphadenomegaly or secondary lesions affecting the abdominal parenchymatous

organs are noted. Diverticulosis of the sigmoid colon. Not free air.

No versmental flaps in the abdomen. Adjust the size and course

of the great abdominal vessels (ATS of the abdominal aorta). Non-pleuro-pericardial effusion.” The ASA score estimated was III.

A bleeding ulcerated lesion of the gastric body was endoscopically found at the level of the posterior wall which couldn’t be

controlled endoscopically.

Operative steps

Laparoscopic access in the peri-umbilical site and under vision

of another 3 trocars in the usual sites; negative exploration for hepatic and / or peritoneal repeats; opening of the gastrocolic ligament with Ultracision and access to the retrocavity of the epiploons, with a finding of neoformation on the posterior gastric wall

(Figure 2), with a prevalent exophytic development, of about 6 cm

of max diameter, facing great curvature, below the fundus. Further mobilization of the stomach: we proceed to sleeve gastrectomy including the aforementioned lesion, with endo gia (4 refills

of 60) (Figure 3). Some hemostatic points on the cut, intracorporeal. Positioning of SNGs; washes, n. 1 drain; layered synthesis of

10 mm breccias.

The operative time was 120 minutes, and there was not significant blood loss. Postoperatively, the patient recovered well and

was discharged by the eight postoperative day. To date the patient

is in good health and disease free; control EGDS one year after

surgery reported normal gastroresection outcomes. Anatomopathological examination reported at the level of the submucosal tunic, a neoformation of the largest diameter (estimated after fixation) of 5.5 cm, of a yellowish-white color, with hemorrhagic

areas, duraelastic consistency, fasciculated appearance and well

demarcated margins is identified. The neoformation does not ulcerate the mucous membrane, it is 0.5 cm from the surgical resection margin and is close to the serous cassock (Figure 4). At the

microscopical examination, a mesenchymal neoplasm consisting

mainly of epithelioid cells, which develops in the context of the

gastric wall (from the submucosal to the subserosal cassock) was

found, with the presence of hemorrhagic areas. Absence of necrosis, calcifications, cellular pleomorphism. Mitotic index: low (2

mitoses / 5 mm2); proliferative activity (evaluated with Ki-67%):

low (2%). Surgical resection margin and deep margin unharmed.

Positivity for vimentin, C-KIT (CD117), DOG-1 (ANO1), CD34 and

negativity for desmin, smooth muscle actin, S100 were detected.

Discussion

Gastric GISTs with dimensions ≤4 cm can benefit from safe endoscopic resections. Gastric GISTs with dimensions >4 cm have a

risk of recurrence or even metastasis, and may require adjuvant

therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), or even the combination of an endoscopic and surgical technique [12].

Complete surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for non-metastatic GIST. It is the very only potentially curative therapy. It is now understood that all GISTs have some malignant potential, while traditionally GISTs were thought to exist on a

spectrum from benign to malignant. Mitotic index and tumor size

and are the two principal attributes, which help stratify malignant

potential of the tumor. These tumors are good candidates for

minimal access surgery, laparoscopic surgery was only considered

for smaller GISTs, up until a few years ago. Studies have shown

that as long as the aforementioned oncological principles are followed, laparoscopic surgery has better short-term outcomes in

the view of decreased shorter hospital stay and blood loss. A recent meta-analysis showed that long-term outcomes were found

to be equivalent to open surgery, even for larger GISTs.

Follow up

Although the risk of recurrence is not zero, patients at very

low risk may not require postoperative follow-up. In low-risk patients, a CT scan examination is recommended every 6 months

for 5 years. Intermediate–high risk patients require postoperative follow-up by CT examination at 3 months in the first 3 years,

then at 6 months for 5 years, then annually. There is a consensus

that abdominal ultrasonography can replace CT evaluation once a

year. In patients that are undergoing TKI therapy, PET/CT is sensitive for assessing treatment response, tumor recurrence or treatment resistance [13].

Conclusion

So, minimally invasive surgery can be considered the first approach for uncomplicated cases, irrespective of their size. The

combined approach both endoscopic and laparoscopic may allow

a better exposure of the tumour which ensure a radical resection

and has shown to be an effective technique [2]. Appropriate patient selection and advanced laparoscopic skills are critical to ensure that oncologic principles in the management of GIST of the

stomach are not compromised.

References

- Arora E, Gala J, Nanavati A, Patil A, Bhandarwar A. Laparoscopic

Transgastric Resection of a Large Gastric GIST: A Case Report and

Review of Literature. Surg J (N Y). 2021; 7: e337-e341.

- Di Buono G, Maienza E, Buscemi S, Bonventre G, Romano G, et

al. Combined endo-laparoscopic treatment of large gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach: Report of a case and literature

review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;77S: S79-S84.

- Gheorghe G, Bacalbasa N, Ceobanu G, Ilie M, Enache V, et al. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors-A Mini Review. J Pers Med. 2021; 11:

694.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology.

- Nishida T, Blay JY, Hirota S, Kitagawa Y, Kang YK. The standard diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on guidelines. Gastric Cancer. 2016; 19: 3-14.

- Joensuu H, Hohenberger P, Corless CL. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2013; 382: 973-983.

- Fulop E, Marcu S, Milutin D, Borda A. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Review on morphology, diagnosis and management. Rom J

Morphol Embryol. 2009; 50: 319-326.

- El-Menyar A, Mekkodathil A, Al-Thani H. Diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: An up-to-date literature

review. J Can Res. 2017; 13: 889-900

- Scarpa M, Bertin M, Ruffolo C, Polese L, D’Amico DF, et al. A systematic review on the clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal

tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2008; 98: 384-392

- Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach.

Int J Surg Pathol. 2002; 10: 81-89.

- Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Pathology

and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006; 23: 70-

83.

- Zhang Y, Mao XL, Zhou XB, Yang H, Zhu LH, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic resection for small (≤4.0 cm) gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. World J Gastroenterol. 2018; 24: 3030-3037.

- Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO–EURACAN Clinical Practice

Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann. Oncol.

2018; 29.