Introduction

Anaesthesia for gynaecological surgeries could be general, epidural, spinal or combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia [1]. Open abdominal myomectomy and hysterectomy are major types of gynaecological procedures and their anaesthesia poses some challenges, especially in developing countries due to socioeconomic factors like poverty, illiteracy, unavailability of anaesthetic drugs and insufficient number of trained Physician Anaesthetists [2,3]. Takai et al [2] found that a high number of the procedures are done under general anaesthesia, but they also noted the use of regional anaesthesia. In another study conducted by Nnaji et al [3], it was observed that combined spinal-epidural (CSE) anaesthesia offers some benefits in terms of better intraoperative and postoperative analgesia in abdominal Myomectomy, but the utilisation rate was very low (1.5%).

General anaesthesia offers better relaxation for gynaecological procedures; however, it could be associated with airway mishaps [4]. While spinal anaesthesia offers good analgesia in an awake patient, most time it does not provide anaesthesia long enough to last the duration of the surgery. Epidural anaesthesia, which is often under utilised in our environment, can offer both intraoperative and postoperative analgesia, and it has the potential to reduce or eliminate the perioperative physiologic stress response to surgery and thereby decrease surgical complications and improve outcomes [5]. Epidural anaesthesia is usually administered for surgeries in the lower abdomen, perineum and lower extremities. Although its onset of action is slow, and sometimes associated with patchy sensory blocks, when properly performed, it can offer good anaesthesia and outlast the duration of prolonged major gynaecological surgeries like abdominal myomectomy and hysterectomy [6,7].

Epidural anaesthesia can be administered as single shot, intermittently, continuously or as patient controlled injection. Some authors have evaluated the addition of adjuvants like dexmedetomidine, clonidine, morphine, fentanyl and neostigmine to local anaesthetic like bupivacaine for epidural anaesthesia in an attempt to potentiate and prolong the analgesic effect [8,9]. However, consideration should also be made to evaluate the haemodynamic effect of combination of local anaesthetics with adjuvants and the techniques of epidural anaesthesia.

There is a perception that continuous epidural infusion of local anaesthetic produces an unchanging block to maintain analgesia and minimise cardiovascular disturbance [10], but this has not been exclusively evaluated. Thus, we conducted a prospective study with the primary aim of determining the differences in the intraoperative haemodynamic changes using continuous or intermittent epidural injection of local anaesthetic agents with opioids. The secondary outcome measures were to determine the differences in the maximum level of sensory block, total volume of epidural drug injection, and side effects that can occur between the two methods of epidural administration.

Methodology

Dorsal hand-foot syndrome (dorsal HFS) is an adverse reaction

induced with taxanes, mainly characterizes as symmetrical,

pleomorphic purplish red plaques, pigmentation, desquamation,

pain, itching and swelling in the skin of the back of the hand and

foot, which can occasionally involve the palmoplantar part [1-4]. In

reviewing the literatures of chemotherapy related dermal toxicity,

dorsal HFS is generally caused by paclitaxel and docetaxel [1,2,5,

6]. And the incidence of docetaxel-induced HFS is approximately

10%, more common than paclitaxel [7]. However, there are no

covers about nab-paclitaxel induced with dorsal HFS. Furthermore,

this untoward dermal toxicity on the dorsal skin of hands and feet

may be classified as HFS in some case reports. At present, there

is no systematic descriptions of the pathogenesis, diagnosis and

treatment of dorsal HFS. In this review, we will present a case of dorsal hand-foot syndrome that induced by nanoparticle albuminbound paclitaxel, and will discuss from the aspects of differential

diagnosis, possible pathogenesis and managements.

Case presentation

A 75-year-old female with advanced gastric cancer and

peritoneal metastasis was admitted to our hospital. In terms

of treatment scheme selection, according to multi-disciplinary

team’s advice, she was recommended to use chemotherapeutic

drugs to treat illness. And since July 14,2020, this patient has been

treated with nab-paclitaxel combined tegafur (Table 1). And prior

to each period, she was premedicated with 5 mg dexamethasone,

5 mg tropisetron, 50 mg diphenhydramine, and 150 mg fosapitan.

On cycle 6 day 14, the patient complained of pain with erythema

or violaceous papules, pruritus, swelling and paresthesia on her dorsum of feet, that prevented her from pursuing activities of

daily life (Figure 2A). To alleviate these unwell symptoms, she

received palliative therapies in another hospital and subsequently

returned to our hospital one month later than originally scheduled.

After admission, she underwent physical examination and results

revealed tender erythema, purplish red papules and plaques,

mildly desquamation and edema on her dorsal feet skin (Figure

2B). She denied the history of taking other drugs and contacting

allergens during chemotherapy. Combined with the patient’s

clinical symptoms and treatment process, in order to determine

whether this series of symptoms of the patient are adverse

reactions of chemotherapy drugs or diseases of blood system, the

patient was further tested by routine blood test, liver function test

and coagulation test, and no abnormality was found in the test

results (Table 2). Therefore, subcutaneous hemorrhage caused by

diseases of blood system was excluded, and skin toxicity caused

by chemotherapy drugs was considered. And her symptoms were

more likely to be considered as dorsal hand-foot syndrome, which

caused by nab-paclitaxel.

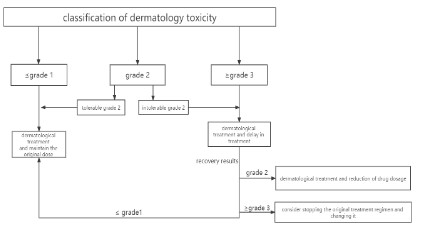

According to the grade of toxic and side effects of

chemotherapeutic drugs, her symptoms were considered as grade

3 or 4 (Table 3) Adverse Event (AE) [8]. Due to the efficacy of the

current chemotherapy regimen was evaluated as stable disease

(shrinkage), so according to AE treatment strategies (Figure 2),

we withdrew albumin-paclitaxel and selected tegafur as her

maintenance treatment [7,9]. She was also advised to undergo

palliative measures by taking low dose corticosteroids, using

hirudoid cream, wearing soft clothes, and reducing skin friction

on feet. We also followed up with this patient. During the followup period, these uncomfortable reactions on the patient’s dorsum

of feet gradually improved, and after the sixth courses of teggio

maintenance treatment, her feet skin returned to be normal

(Figure 2C). The patient’s follow-up results further confirmed that

albumin-paclitaxel was the offending agent.

Table 1: The patient’s treatment strategy and treatment course.

| Cycle |

Day |

Treatment |

| Cycle 1-2 |

D1 |

albumin-bound paclitaxel 260 mg/m² peritoneal perfusion |

| D8 |

albumin-bound paclitaxel 260 mg/m² intravenous |

| D1-D14 |

Tegafur 80mg/m² ora |

| Cycle 1-2 |

D1 |

albumin-bound paclitaxel 260 mg/m² intravenous |

| D8 |

albumin-bound paclitaxel 260 mg/m² intravenous |

| D1-D14 |

Tegafur 80mg/m² oral |

Table 2: The patient’s laboratory test results.

| December 12,2020 |

| Blood routine |

RBC: 3.78 x 1012/L |

HGB: 114 g/L |

PLT: 192 x 109/L |

PLT: 192 x 109/L |

|

|

| Coagulation routine |

TT: 17.0s |

APTT: 26.4s |

PT: 10.4s |

INR: 0.88 |

PT |

FB |

|

|

|

|

|

A: 130% |

G: 4.17 g/L |

| Liver function |

TBIL: 9.1 umol/L |

DBIL: 1.7 umol/L |

IBIL: 7.4 umol/L |

Globulin: 24.7 g/L |

|

|

Table 3: Classification criteria of HFS according to NCI and WHO.

| Grade |

NCI |

WHO |

| 1 |

Minimal skin changes or dermatitis (rash, edema, hyperkeratosis) without pain |

Dysesthesia/paresthesia, tingling in hands and feet |

| 2 |

Skin changes (peeling, blisters, bleeding, cracks, edema, hyperkeratosis) with

pain, limiting instrumental ADL |

Discomfort in holding objects or in walking, edema or/and erythema

without pain |

| 3 |

Severe skin changes (peeling, blisters, bleeding, cracks, edema, hyperkeratosis)

with pain; limiting self-care ADL |

Painful erythema and edema in palms and soles, and around fingernails

and toenails |

| 4 |

|

Desquamation, ulceration, blistering, severe pain |

NCI: the American National Cancer Institute; WHO: the World Health Organization; ADL: activities of daily life.

Discussion

Among the side effects related to chemotherapeutic drugs,

dermatological toxicity is the most common adverse reaction.

Common cutaneous adverse reactions include eruption, HandFoot Syndrome (HFS), dorsal hand-foot syndrome, Periarticular

Thenar Erythema With Onycholysis (PATEO), and Hand Foot Syndrome Reaction (HFSR). Hand-Foot Syndrome (HFS), one of the

most universal adverse effects commonly characters as palmoplantar numbness, tingling, burning pain, erythema, pigmentation, with or without edema on palms and soles, can be induced

with a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, such as capecitabine,

doxorubicin, 5fluorouracil, taxanes and so on [10-12]. Compared

with HFS, the incidence of dorsal hand-foot syndrome is much

lower.

Albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), a novel, solventfree taxane drug, which has demonstrated advantages in delivering a higher dose of paclitaxel to foci and reducing the incidence

of severe adverse reactions. The common toxicities of nab-paclitaxel include anaphylactic reactions, myelosuppression, mucositis, fatigue and neuropathy [13].

Compared to paclitaxel and docetaxel, albumin-paclitaxel

caused very few dermal toxicity reactions. Here, we report a case

of dorsal HFS induced by nab-paclitaxel rather than tegeo-guided

HFS. After withdrawing albumin paclitaxel, the patient’s discomfort gradually eliminated and the rash did not recur. The follow-up

result of this patient also authenticated that the skin toxicity was

caused by albumin paclitaxel. This further reminds us that timely

and accurately identify dorsal HFS is crucial for the choice of subsequent treatment. However, there is no systematic description

about dorsal hand-foot syndrome from clinical symptoms, possible pathogenesis and effective managements.

First of all, in terms of diagnosis, dorsal hand and foot syndrome should be distinguished from other cutaneous toxic reactions induced with chemotherapeutic drugs, such as HFS, PATEO,

HFSR and so on. In clinical symptoms characterizes: hand-foot

syndrome is initially manifested as palmoplantar numbness, tingling, burning pain, and then erythema, with or without edema,

desquamation. HFS is mainly founded on palms and soles that

may be related to the large concentration of microcapillaries and

sweat glands in these areas. PATEO showed purplish red plaques

at the protrusions of large and small fish and on dorsum of hands,

accompanied with nail changes that frequently progress to onycholysis. However, dorsal HFS mainly characters as symmetrical, pleomorphic purple patches, pigmentation, desquamation, with

or without pain, itching and swelling appeared in the affected

parts. It focuses on the dorsum of hands and rare on the dorsum

of feet or around the ankle that may be related to sun-exposed [7,

14-17]. In addition to distinguishing from other dermatology toxicity caused by chemotherapeutic drugs, dorsal HFS should also

be distinguished from subcutaneous bleeding caused by blood

system diseases, such as thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia

and so on. They can be identified by perfecting laboratory related tests. As for histopathological characteristics, relevant studies

have shown that HFS and dorsal HFS are similar. HFS’s histopathological feature is hyperkeratosis of the overlying epidermis,

spongiotic changes, focal vacuolization with necrotic and dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the basal cell layer. The histopathological

characteristics of dorsal HFS is Keratinocyte apoptosis, dyskeratosis, atypical mitotic figures, abnormal maturation of keratinocytes [1,18,19]. In terms of occurrence mechanism, different chemotherapy drugs cause HFS by different mechanisms. The exact

mechanisms governing HFS and dorsal HFS are unclear. Possible

pathogenesis of HFS are as follows: C0X-2-mediated inflammatory

response; chemotherapeutic drugs accumulated in small sweat

ducts; enzymes related to catabolism of chemotherapeutic drugs,

such as thymidine phosphorylase and Dihydropyridine Dehydrogenase (DPD) that are related to disassemble 5-FU; microcapillary

damage leading to drugs extravasation and consequent dermal

toxicity [14,15,20]. However, the mechanisms of dorsal HFS have

not been systematically studied.

According to the types of skin toxic reactions caused by taxol,

the possible pathogenesis are inflammatory reactions, solvent

response and the direct cytotoxic effect. The optimal therapeutic

for HFS and dorsal HFS has not yet been determined. Currently,

all dermatology toxicities’ managements mainly involve three aspects: patient’s self-monitoring, drug treatment and chemotherapeutic dose management [21,22]. During the entire treatment,

patients are advised to wear suit clothes, avoid strenuous exercise, refrain from injury and fraction of hands and feet. Except essential ways, patients with dorsal HFS are recommended to wear

ice gloves, caps and avoid sun exposure [22]. In terms of symptomatic treatment measures, patients may relieve discomfort by locally using urea cream, taking medicines such as COX-2 inhibitors,

pyridoxine, topical corticosteroids, vitamin E and herbal remedies

[23-26]. Chemotherapeutic dose management means that when

symptoms remain severe after symptomatic treatment, dose reduction or chemotherapy discontinuation may be considered

[7,9]. Although the managements of other cutaneous adverse effects and dorsal HFS are similar, enhanced awareness of how to

identify and treat dorsal HFS is crucial for prompt treatment and

subsequent options.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the first case presentation of dorsal handfoot syndrome developed by nab-paclitaxel. Currently, the mechanism and specific therapeutic measures for dorsal hand-foot

syndrome have not been precisely defined, more further studies

are needed to solve these problems.

How to promptly identify dorsal hand foot syndrome is pretty

essential to improve the quality of life and provide duly treat strategies for patients receiving chemotherapy.

Declarations

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The author is responsible for all

aspects of the work to ensure that issues related to the accuracy

or completeness of any part of the work are properly investigated

and resolved. This case report has passed the ethical approval of

the First Hospital of Jilin University, and there is no conflict of interest when writing this article.

References

- Brandon Z, Kristin L, Jeave R, Jodi S. A Paclitaxel-Induced Variant

of Hand-Foot Syndrome Affecting Dorsal Surfaces. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2021; 48.

- Patel J, Ringley JT, Moore DC. Case series of docetaxel-induced

dorsal hand–foot syndrome. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety.

2018; 9.

- Plummer RS, Shea CR. Dermatopathologic effects of taxane therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010; 65.

- C. ZG. Acute cutaneous reactions to docetaxel, a new chemotherapeutic agent. Archives of Dermatology. 1995; 131.

- Mirna F, Nagi E-S, Ali S. Hand-foot syndrome with docetaxel: A fivecase series. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2008; 28.

- S KP, P KP, A PA, Nahush T, Vijay B, Honey P. Rare occurrence of

hand-foot syndrome due to paclitaxel: A rare case report. Indian

journal of pharmacology. 2018; 50.

- Vincent S, R LN, Henri R, R BV, Laurence G, Marion D, et al. Dermatological adverse events with taxane chemotherapy. European

journal of dermatology: EJD. 2016; 26.

- Nagore E, Insa A, Sanmartín O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced

palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (‘hand-foot’) syndrome. Incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000; 1:

225-234.

- Nikolaou V, Syrigos K, Saif MW. Incidence and implications of chemotherapy related hand-foot syndrome. Expert Opin Drug Saf.

2016; 15: 1625-1633.

- Tebbutt NC, Wilson K, Gebski VJ, Cummins MM, Zannino D, et al.

Capecitabine, bevacizumab, and mitomycin in first-line treatment

of metastatic colorectal cancer: results of the Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group Randomized Phase III MAX Study. J Clin

Oncol. 2010; 28: 3191-3198.

- Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, Im YH, Lee ES, et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N Engl

J Med. 2017; 376: 2147-2159.

- Tagawa N, Sugiyama E, Tajima M, Sasaki Y, Nakamura S, et al. Comparison of adverse events following injection of original or generic

docetaxel for the treatment of breast cancer. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 2017; 80: 841-849.

- Fei H, Jiaxuan L, Xin S, Zijing W, Qiao L, et al. Adverse Event Profile

for Nanoparticle Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel Compared With Solvent-Based Taxanes in Solid-Organ Tumors: A Systematic Review

and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. The Annals of

pharmacotherapy. 2021.

- Martschick A, Sehouli J, Patzelt A, Richter H, Jacobi U, et al. The

pathogenetic mechanism of anthracycline-induced palmar-plantar

erythrodysesthesia. Anticancer Res. 2009; 29: 2307-2313.

- Lou Y, Wang Q, Zheng J, Hu H, Liu L, Hong D, et al. Possible Pathways of Capecitabine-Induced Hand-Foot Syndrome. Chem Res

Toxicol. 2016; 29: 1591601.

- Yokomichi N, Nagasawa T, Coler-Reilly A, Suzuki H, Kubota Y, et al.

Pathogenesis of Hand-Foot Syndrome induced by PEG-modified

liposomal Doxorubicin. Hum Cell. 2013; 26: 8-18.

- Rzepecki AK, Franco L, McLellan BN. PATEO syndrome: periarticular thenar erythema with onycholysis. Acta Oncol. 2018; 57: 991-

992.

- Antonio C, Tecla T, Gladys H-T, George K. Paclitaxel-induced neutrophilic adverse reaction and acral erythema. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2011; 91.

- Gordon KB, Tajuddin A, Guitart J, Kuzel TM, Eramo LR, et al. Handfoot syndrome associated with liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin therapy. Cancer. 1995; 75: 2169-2173.

- Van Kuilenburg AB, Meinsma R, Zoetekouw L, Van Gennip AH. Increased risk of grade IV neutropenia after administration of 5-fluorouracil due to a dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency:

high prevalence of the IVS14+1g>a mutation. Int J Cancer. 2002;

101: 253-258.

- Johannes J M K. Management of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced

hand-foot syndrome. Oncology reviews. 2020; 14: 442.

- Jiexiu C. How to conduct integrated pharmaceutical care for patients with handfoot syndrome associated with chemotherapeutic

agents and targeted drugs. Journal of oncology pharmacy practice

: official publication of the International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners. 2021; 27: 919-929.

- Chen LT, Han TP, Wai TK, Wei HT. Effect of Urea Cream on HandFoot Syndrome in Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: A Meta-analysis. Cancer Nursing. 2021.

- Rong-Xin Z, Xiao-Jun W, Shi-Xun L, Zhi-Zhong P, De-Sen W, Gong C.

The effect of COX-2 inhibitor on capecitabine-induced hand-foot

syndrome in patients with stage II/III colorectal cancer: a phase

II randomized prospective study. Journal of cancer research and

clinical oncology. 2011; 137.

- . Lian S, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhao Q. Pyridoxine for prevention of

hand-foot syndrome caused by chemotherapy agents: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021; 46: 629-635.

- Bozkurt Duman B, Kara B, Oguz Kara I, Demiryurek H, Aksungur E.

Hand-foot syndrome due to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma

treated with vitamin E without dose modification; a preliminary

clinical study. J buon. 2011; 16: 759-764.