Introduction

The most common cause of death from female reproductive

cancers is ovarian cancer. In addition to the lack of early-stage illness symptoms, there also are no reliable screening techniques,

which leaves two thirds of patients with advanced-stage ovarian

cancer when they are diagnosed. The development of efficient

screening tests and their implementation in a clinical setting are

of utmost importance to improve the prognosis of ovarian cancer

by prompt detection because the 5-year survival rate is up to 90%

in patients with early-stage disease while it is less than 20% in

those with advanced-stage disease [1]. A deadly form of gynecologic cancer that develops from an ovarian tumor is called ovarian

cancer. Initially, symptoms are typically subtle and may include

bloating, pelvic pain, and difficulty eating, and excessive urination, and they can be mistaken for other conditions. Ovarian cancers are categorized as «epithelial» and are thought to develop

from the ovary’s surface in the majority (>90%) of cases. However,

some data point to the possibility that certain ovarian malignancies may potentially originate in the fallopian tube. These ovarian cancer-mimicking fallopian cancer cells are believed to exist.

Some varieties (germ cell cancers) arise from supporting cells or

from egg cells. Gynecologic cancers, including ovarian cancers, fall

within this category [2]. According to Globocan http://globocan.

iarc.fr/Default.aspx), ovarian cancer had 238,619 incident cases

in 2012, making it the seventh most prevalent cancer overall and

the leading cause of death from gynecological cancers. It is listed

as the second most prevalent gynecological cancer in developing

nations with 17,755 incident cases in 2012 and the fourth most

prevalent cancer in women overall. Basically, industrialized nations have the highest ovarian cancer incidence rates. North America and Western Europe had the highest incidence rates (10.7 per

100,000 person-years and 13.3 per 100,000 person-years, respectively), whereas North Africa has the lowest incidence rates (2.6

per 100,000 person-years). However, in a hospital-based data

set from the National Cancer Institute, Gezira University, Central Sudan, and Radiation Isotopes Center in Khartoum, collected between 2000 and 2006, ovarian cancer accounted for 6.8%

(949) of all recorded cancers (n=226,652) and was ranked the

sixth most common cancer for both genders. The incidence rate

of ovarian cancer in the entire Sudan has not yet been determined. In addition, ovarian cancer ranked fourth among all female

cancers in a more recent data set (2009-2010) from the National

Cancer Registry for the Khartoum State alone, with an estimated

incidence rate of 188 per 100,000 people, a gender-specific rate

of 8.0 per 100,000 people, and an age-standardized rate (ASR)

of 7.0 per 100,000 people. Due to the lack of death certificates,

the survival rate for ovarian cancer in Sudan has also never been

reported, and the majority of patients who presented with advanced-stage disease did not receive complete examinations or

symptomatic treatment [3]. The precise cause of ovarian cancer

is still mostly unknown. There are various factors that seem to

influence the likelihood of getting ovarian cancer [4]. The risk is

higher for older women who have never given birth and for those

with first- or second-degree relatives who have the illness. Mutations in particular genes, most notably the BRCA1 and BRCA2

genes of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, can result in

hereditary forms of ovarian cancer. Women who are infertile, suffer from endometriosis, or use postmenopausal estrogen replacement treatment are at higher risk [5]. The epithelial surface of the ovary accounts for around 90% of ovarian neoplasms, with the

remaining 10% coming from germ cells or stromal cells. Serous

(30-70%), endometrioid (10-20%), mucinous (5-20%), clear cell

(3-10%), and undifferentiated (1%), are the different categories

for epithelial neoplasms. For each of these subtypes, the 5-year

survival rates are 20-35%, 40-63%, 40-69%, 35-50%, and 11-29%,

respectively [6,7,8]. The ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneum

cancer classifications are combined in the updated, revised FIGO

staging system. It is founded on data gathered from exploratory

surgery [9]. Histological grading, which is connected with prognosis, is used to further subclassify epithelial malignancies of the

ovary and fallopian tube. This approach does not grade non-epithelial cancers. There are two grading schemes used. According

to an architecture with a one-step upgrade, if there is substantial

nuclear atypia, nonserous carcinomas (most endometrioid and

mucinous) are graded in the same way as uterine cancers. GX:

Grade not measurable G1 is a well-differentiated group, followed

by G2 and G3, which are moderately and poorly differentiated [9].

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and passed by the Ethics

Committee of the Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of

Khartoum. Written informed consent was obtained from enrolled

patients and apparently healthy volunteers.

Study design, sites, and duration

A prospective, hospital-based was conducted over two years

(January 2014-December 2015) at tertiary-referred hospitals.

Study population

One hundred and twelve women with histologically-confirmed

ovarian cancers (cases).

Statistical analysis

The collected data was analyzed using SPSS version 16; frequencies, t-test, correlation and significance for patients data. P

value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

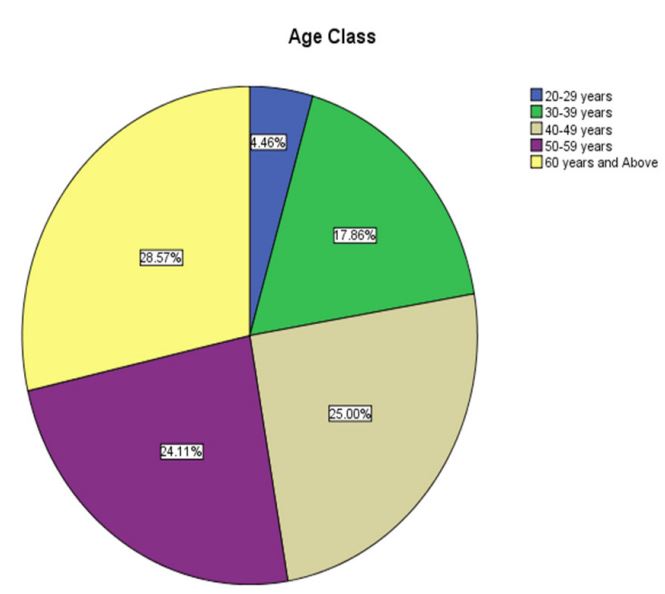

The average patient age, according to demographic statistics,

was 46.5 27.5 years. 90% of the women in this cohort ranged

in age from 30 to 70. (figure1). Ovarian cancer is not prevalent

(p=0.5) in women under the age of 30 (frequency=4.5%) or over

the age of 70 (frequency=1.7%), although the most common age

group is over 60. (Table1). In the previous six months, more than

40% (50/112, 44.6%) of the patients experienced symptoms of

abdominal discomfort, pelvic pain, and irregular bleeding (Table

2). 38/112 (33.9%) of the patients had symptoms for more than a

year, compared to 6.4% for two years and 14.3% for three years,

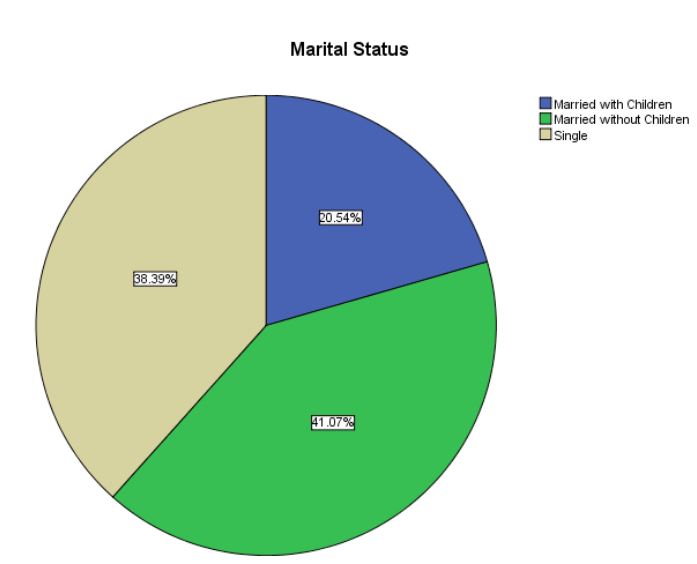

respectively (Table 3). Eighty percent of the patients (89/112)

were childless. A fifth (20.5%, 23/112) were married and had

children, whereas a third (44/112, 39.3%) were unmarried, 4and

0.2% (45/112) were married but had no children. Thus, women

without children and single women made up the bulk of patients

[79.5%] (Table 4). Breast and colon cancers were the most frequent concomitant cancers, whereas endometrial, colon, lung,

breast, and brain cancers were the least prevalent (6/112, 5.4%) among the patients (Table 5). The majority of patients in the research cohort (81.1%, 91/112) had serous adenocarcinoma of the

ovaries. More than half of the patients had advanced stages, with

stages III and IV present in 31.3% and 26.8% of patients, respectively. A minority (3.6%) of patients were diagnosed with the early

stages, or stage I, whereas a fifth (19.6%) of patients came with

stage II. With 1.8% at stage II, 4.5% at stage III, and 3.6% at stage

IV, mucinous types were observed in 11 patients (11/112, 9.9%).

10.7% (6/112) of the patients had the endometroid type, with

stage I patients having 3.6% and stage III patients having 1.8%. In

the minority, germinoma (1/112, 0.8%) and poorly differentiated

carcinomas (2.7%, 3/112) were detected (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 1: Distribution of the patients according to age group.

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative

Percent |

p Value |

| 20-29 years |

5 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

0.507 |

| 30-39 |

years |

20 |

17.9 |

17.9 |

22.3 |

| 40-49 |

years |

28 |

25.0 |

25.0 |

47.3 |

| 50-59 |

years |

27 |

24.1 |

24.1 |

71.4 |

| 60 years and Above |

32 |

28.6 |

28.6 |

100.0 |

|

| Total |

112 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Table 2: Distribution of symptoms and signs among studied patients.

| Sign and symptoms |

Frequencies and percentages

|

Ascites

Abdominal

discomfort

Pelvic pain

and swelling

Irregular

bleeding

|

14/112 (12.5%)

52/112

(46%)

32/112 (29%)

14/112

(12.5)

|

Table 3: Duration of the symptoms of diseases among the study subjects.

| Duration of disease |

No & frequency |

| Less than 6 months |

50/112 (45%) |

| 6-12 months |

38/112 (34%) |

| 12-18 months |

2/112 (1.8%) |

| 18-24 months |

4/112 (3.6%) |

| 24-30 months |

2/112 (1.8%) |

| 30-36 months |

14/112 (12%) |

| 36-42 months |

2/112 (10.8%) |

Table 4: Marital status of the study women.

| Variable |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid

Percent |

Cumulative

Percent |

t-test |

p value |

| Married with children |

23 |

20.5 |

20.5 |

20.5 |

|

|

|

Married without children

|

46 |

41.1 |

41.1 |

61.6 |

9.795 |

0.000 |

| Single |

43 |

38.4 |

38.4 |

100.0 |

|

|

| Total |

112 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Table 5: Association of other tumors with ovarian cancer.

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

P value |

correlation |

| No |

106 |

94.6 |

94.6 |

94.6 |

|

|

| Yes |

6 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

100.0 |

0.132 |

.143 |

| Total |

112 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Table 6: Histological distribution among the patients.

| Histological type |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative

Percent |

| Serious Adenocarcinoma |

91 |

81.2 |

81.2 |

81.2 |

| Mucinous |

11 |

9.8 |

9.8 |

91.1 |

| Endometroid |

6 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

96.4 |

|

Poorly Differenyiated

Carcinoma

|

3 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

99.1 |

| Germinoma |

1 |

.9 |

.9 |

100.0 |

| Total |

112 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Table 7: Stages of different hispatternsal pattern of disease.

| Disease Stage |

Frequency |

Percent |

| 3 |

42 |

37.5 |

| 4 |

34 |

30.4 |

| 2 |

23 |

20.5 |

| 1 |

11 |

9.8 |

| Total |

110 |

98.2 |

| Missing |

2 |

1.8 |

| Total |

112 |

100.0 |

Discussion

Currently, ovarian cancer is the most fatal gynecologic malignancy affecting Sudanese women. Unfortunately, the subtle

symptoms of this disease cause the majority of cases to appear

late. It is worse because there are no sensitive and accurate testing for this cancer. In our study, the bulk of the patients were

older than 60, although it was far less frequent in people under 30

and older than 70. The findings concurred with those of a study

conducted in the United States, which found that women between

the ages of 60 and 64 had the highest prevalence (10). According

to this study, getting married and having kids greatly lowers the

risk of acquiring ovarian cancer. Most of the patients we saw had

never had children. This is in line with the U.S. Third National Cancer Survey [1969-1971], which found that women who had never

married were 60-70% more likely to get ovarian cancer than those

who did [11]. While irregular vaginal bleeding and ascites were

uncommon, the most prevalent symptoms were ambiguous (abdominal discomfort and pelvic pain), which explains the disease’s

late manifestation during the first year of development. This is

consistent with earlier findings from the area and around the

world [12]. A handful of our patients received an early diagnosis, but more than half of them had serous adenocarcinomas of

the ovaries that were in advanced stages. This is consistent with

earlier findings from the area and around the world [13]. Fewer

patients had other histological types visible. The findings did not

agree with those from the rest of the world, which indicated

that endometroid cancer predominated [14]. 6/112, or 5.4%, of

the patients also had endometrial, colon, lung, breast, or brain

tumors at the same time as their ovarian cancer. Compared to

other cancers, breast and colon cancer appear to occur more frequently together. This is consistent with earlier findings from the

area and around the world [15]. This could be explained by the

fact that BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes confer increased susceptibility

to cancer is more commonly seen in patients with breast, colon,

and ovarian cancers in agreement with the report of Wooster and

colleagues [16-18].

Conclusion

The majority of Sudanese women who get ovarian cancer are

childless and unmarried. Below 30 years old, it is less frequent,

and over 60 years old, it is more prevalent. Serous adenocarcinoma is the predominant histological type, with stage 3 being the

most frequent.

Declarations

Acknowledgments: The investigating team would like to thank

the staff of the Department of Immunology and Clinical Pathology, Institute of Endemic Diseases, and the University of Khartoum

for their great support. Full appreciation to the Department of

Obstetrics & Gynecology at Omdurman Military Hospital, for the

extra help, performed by their patients, and also many thanks to

Khartoum Radiation & Isotopes Centre, for making it possible to

conduct this research.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from

funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest

of any sort, financial or otherwise.

References

- Lee J, Kim H, Suh D, Kim M, Chung H, Song Y. Ovarian Cancer Biomarker Discovery Based on Genomic Approaches. Journal of cancer prevention, 2013; 18: 298-312.

- Piek JMJ, Van Diest PJ, Verheijen RHM. Ovarian carcinogenesis: An alternative hypothesis. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2008; 622: 79-87.

- Dafalla O. Abuidris, Hsin-Yi Weng, Ahmed M. Elhaj, Elgaylani Abdallah Eltayeb, Mohamed Elsanousi, Rehab S. Ibnoof, and Sulma I. Mohammed. Incidence and survival rates of ovarian cancer in low-income women in Sudan. Journal of Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2016; 5(6): 823-828.

- Hippisley-Cox, J. & Coupland, C. Identifying women with suspected ovarian cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of algorithm. BMJ (Clinical research edition.). 2012; 344(7841): d8009.

- Pearce, C, Templeman C, Rossing MA, Lee A, Near AM, Webb PM. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis of case-control studies. The Lancet Oncology. 2012; 13(4): 385-394.

- Björkholm E, Pettersson F, Einhorn N, Krebs I. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factors in ovarian carcinoma. The radiumhemmet series 1958 to 1973. Acta radiologica. Oncology. 1982; 21(6): 413-9.

- Sorbe, B., Frankendal, B. & Veress, B. Importance of histologic grading in the prognosis of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1982; 59(5): 576-82.

- Högberg, T., Carstensen, J. & Simonsen, E. Treatment results and prognostic factors in a population-based study of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 1993; 48(1): 38-49.

- Jonathan S. Berek,Malte Renz,Sean Kehoe,Lalit Kumar,Michael Friedlander. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2021; 155(1): 61-85.

- Monica R, McLemore, Miaskowski, Christine RN, Aouizerat, Bradley E, Chen, Lee-may Dodd, Marylin J. Epidemiological and Genetic Factors Associated With Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2009; 32(4): 281-288.

- Noel S. Weiss, M.D. John L. Young, Jr., Dr. P.H. Gilbert J. Roth, M.D. Marital Status and Incidence of Ovarian Cancer: The U. S. Third National Cancer Survey. 1969-1971. Journal of National Cancer Institute. 1977; 58 (4): 913-915.

- Bankhead C, Collins C, Stokes-Lampard H, Rose P, Wilson S, Clements A, et al. Identifying symptoms of ovarian cancer: a qualitative and quantitative study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008; 115: pp 1008-10.

- Rosen DG, Yang G, Liu G, Mercado-Uribe I, Chang B, Xiao XS. Ovarian cancer: pathology, biology, and disease models. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition). 2009; 14: 2089-2102.

- Tanvir I., Riaz S, Hussain A, Mehboob R, Shams M, Khan H. Hospital-based study of epithelial malignancies of endometrial cancer frequency in Lahore, Pakistan, and common diagnostic pitfalls. Pathology Research International, 2014; 2014(10): 5.

- Phelan CM, Iqbal J, Lynch H T, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Moller P, t al. (2014). Incidence of colorectal cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. British Journal of Cancer. 2014; 110: 530-534.

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature, 1995; 378: 789-792.

- Thompson D, Easton D Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in cancer risks, by mutation position, in BRCA2 mutation carriers. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001; 68:410-419.

- Thompson D, Easton DF. Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Journal of Nationl Cancer Institute. 2002; 94: 1358-1365